Human Interest Photos, with excerpts from Cabeza

Cactus “decorated” by the “undocumented” “migrants.” The latest is that Phoenix, which thanks to its burgeoning population — I wonder why — is out of water, so the powers that be are planning a desalinization plant in Mexico on the Gulf of California. A huge array of solar panels will be constructed somewhere and a wide corridor with power lines and pipeline will be constructed — straight through Organ Pipe National Monument — to take the electricity down to power the plant and pipeline pumps, and bring the water back.

See Chapter 2 of Cabeza:"In retrospect, that was just the beginning. In 2003 I learned it was a whole brave new world out there: Two million [now 5,000,000] UDAs (undocumented aliens) a year crossing along the entire U.S./Mexican border. Local hospitals going bankrupt because they’re required to administer free emergency medical care to the indigent, including illegal aliens. More ominously a ranger advised me that the previous year one of his brethren had been shot by drug smugglers in the adjacent Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Beneath his bulletproof vest. With an AK-47. Dead. I learned that drug and immigrant smugglers had stopped drivers in remote parts of the Monument demanding money, food and water, rides, or tires. I was warned that if we see people seemingly in need, well, they might be in need . . . but might not be quite the type we’d want to help. Arizona just happens to be number one in the nation in stolen vehicles per capita. Because the need is so great. A four-wheel-drive pickup camper? How perfect! Almost as an afterthought the ranger said there’d been a lot of resource damage.

Photo showing I had successfully completed my PhD on extracting two wheel drive pickups from Utah mud holes.

Cabeza, Chapter 12:"I drove up an unmaintained gravel road to about 7000 feet, then pulled off and parked in a hunters’ or ranchers’ campsite. The next day it poured so I stayed in the cabin, sitting and going for a few short walks. The following morning seemed more promising so I drove out toward the road and. . . .

This is my first four-wheel-drive pickup, a gift from my father. I made the photo into a card and mailed it to him with the words “Thanks!” This is on the way to the Maze on the most rugged four-wheel-drive stretch I’ve seen. Two times coming off a rock ledge the front wheel bearings were damaged — but fortunately we made it home. Always check your wheel bearings for play after driving over such a road. If damaged they could actually overheat and the whole axle fall off.

Anne in proper desert attire — except for the hiking stick which we later retired in favor of trekking poles — with their killer wrist straps.

Chapter 7: . . ."Now the reader is probably thinking that we are real dummies to hike using trekking poles with killer wrist straps, and perhaps the reader is right. When I started backpacking I had to have a hiking stick just like Colin Fletcher. And it served me well for many years, one advantage being you can slide your hand up and down as the terrain changes. Then about eight years ago, a month after limping out of the Adirondacks on hobbled knees, there was an article in Backpacker: “Save Your Knees with Trekking Poles.” And they did, making it possible for us to continue these trips. Since then we have done very careful, ever more intensive strength training of all parts of our bodies and my knees are better than new, but we still wouldn’t dream of a trip like this without poles.

We had stopped feeding the birds a long time ago because of the bears, which the New York State Department of environmental conservation advises (for people living in densely wooded rural areas like us). But our neighbors to the west and the east still feed the bears — I mean the birds. I regularly see their scat in the yard and every few months I see them crossing the clearing to the northwest of our house. So last month I saw a baby, possibly a yearling, and presumably the mother crossing. But when the mother got halfway across she looked up at our house, and thought to herself, "Hey, maybe they've got a birdfeeder up there, too." So she changed direction and made straight for our front door. From there she went around to the garage, but then she came back to the living room window where I snapped this photo. It was fun up until now, but then she went up on the porch, climbed up on the bench on the right side of the porch and tried to get in the window — which was fully open! — right next to it! She even put her paw marks on the window. See below. At this point I started yelling at her, "Go away. Go away!" and banging two pieces of wood together… and she did at that point depart from the scene. I have since installed iron bars across that window — since I like to keep it open all summer — and the same with two basement windows. Haven't seen them since… and the neighbors keep feeding the bears — I mean the birds.

I sent this photo to the neighbor to the east (called Jack Jones in Cabeza). He replied: "Nice photo. Did you ask her to smile?" Me: "No. She looked like she was in a bad mood."

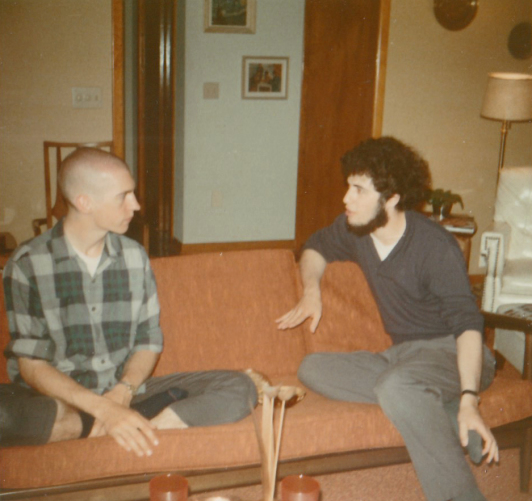

This was perhaps the last time I saw Steve (at my parents house), who introduced me to Bach’s Art of the Fugue. He moved on to Coltrane. I tried Coltrane. I returned to Bach. — July 1, 1970. We had bumped into each other in Grand Central Station on our way home to visit our parents. I had had my flunk out sesshin at the Zen Center the previous January after which I stopped going to the center. But I never stopped sitting. I always continued to sit. But I had thought that by shaving my head I would simplify my life and it would somehow inspire my practice. Fat chance. I probably only shaved it once.

Steve meanwhile was working on his PhD in nuclear physics, and this is what he was likely explaining to me at that moment of the photos. I think the expression on my face shows how dubious I was that this would lead to a complete understanding of… Everything. A significant amount of daily sitting meditation — by means of my non-method involving “free won’t” (just being with one’s own mind; see Cabeza, especially The Unfree Will chapter) — is utterly necessary for such, in my view. But the greatest works of music, especially those of Bach and Beethoven, can help provide direction.

Note "Starry Night" on the wall.